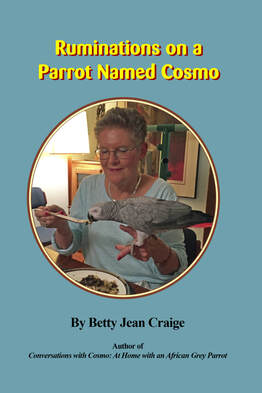

Cosmo, a talkative, smart, funny, and affectionate African Grey parrot, is the subject of two of Betty Jean's books: Conversations with Cosmo: At Home with an African Grey Parrot, published in 2010, and Ruminations on a Parrot Named Cosmo, published in 2021.

- Ruminations on a Parrot Named Cosmo was named Winner in the Animals/Pets category of the New York City Big Book Award, Winner in the Non-Fiction category of the Best Independent Book Awards, Finalist in the Narrative Non-Fiction category of the 2021 International Book Awards and in the 2021 Best Book Award, First Place in the Animals/Pets category of the Next Generation Indie Book Awards for 2021, Finalist in 2022 Global Book Awards, and 2022 Independent Press Award Distinguished Favorite.

- It received a 5-Star Review from Readers’ Favorite.

See Online Book Club review of Ruminations.

See Kirkus review of Ruminations.

See Bookview review of Ruminations.

See Discovery review of Ruminations by Julia Hoover.

See Readers' Favorite review of Ruminations by Shrabastee Chakraborty

See Boom Magazine article, "An Afternoon with Cosmo" by Tracy Coley

Hear Cosmo talk on YouTube: cosmotalks

"The pages convey her deep empathy and adoration for Cosmo, her pet dogs, as well as her backyard visitors. Undoubtedly one of the best books I have ever read, this filled my brain with wonder and my heart with warmth." 5 Stars

--Readers' Favorite

A laugh-out-loud funny, informative, and tender read for animal lovers; Cosmo is unforgettable.

--Kirkus Review

Ruminations on a Parrot Named Cosmo was named Winner in the Animals/Pets category of the New York City Big Book Award, Winner in the Non-Fiction category of the Best Independent Book Awards, Finalist in the Narrative Non-Fiction category of the 2021 International Book Awards and in the 2021 Best Book Award, First Place in the Animals/Pets category of the Next Generation Indie Book Awards for 2021, and 2022 Independent Press Award Distinguished Favorite in the category of Mystery. It received a 5-Star Review from Readers’ Favorite.

Here is a sneak peek at Ruminations on a Parrot Named Cosmo.

One morning not long ago I awoke to the extremely loud call of a Northern cardinal. It sounded as if the bird were in my house. Well, a bird was, but not a cardinal. Cosmo was spiritedly mimicking the wild avian inhabitants of our woods.

I heard: "purdy purdy purdy whoit whoit whoit whoit," the cardinal. Then, "oo-wah-hooo, hoo-hoo," a Mourning dove. Then "peter peter peter," a Tufted titmouse. The sounds of nature.

How lovely.

Then "Beep beep beep beep beep." Whoa! What was that? Oh yes, a truck backing up.

Finally I heard, in my voice, "I'm here! Come here! Cosmo wanna go up!" I got up and let Cosmo out of her cage.

Cosmo is a superb mimic. She must have superb hearing.

Birds' hearing is generally much more acute than human hearing. Some researchers describe it as "more detailed." Birds can distinguish sounds from each other that blend together for us humans—unless we record and analyze them electronically. They can discriminate not only a huge variety of calls from different birds, but also different calls from the same bird.

Cosmo fooled me into thinking I had a cardinal in my house, but she probably didn't fool the cardinal's mate. And she probably didn't understand what the cardinal was saying to his mate.

The Northern cardinal has some sixteen different calls for different purposes—for locating his mate, for sounding an alarm, for warning intruders on his territory, etc. Cosmo would not have understood the calls.

By the way, Cardinals have regional accents, according to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Like us humans.

Like parrots. Every African Grey family has its own accent. And every African Grey flock has its own accent. Biologist Michael Schindlinger says flocks of parrots develop their own dialect because young parrots mimic the calls of the other flock members.

Grey babies have a lengthy learning period. They don't reach sexual maturity until they are six years old, on average. In their first year, when they stay close to their parents, the fledglings learn their calls from their parents and the rest of their flock. They are not born knowing how to how to make a specific chirp. Each family, as we have learned from digital recordings, has its own accent.

Whale pods too have their unique accent. Whales communicate with a system of vocal signals, and whales in different regions of the ocean have different dialects. The enormous Blue whales, who vocalize at frequencies too low for humans to hear, use sound to navigate, find a mate, and alert each other about food sources. Their signals can travel a thousand miles through the water. When the male and female whales get together, they may discover they have different accents.

And crows from different regions have different accents.

Those who have regional accents must do some learning from each other. And they must hear very well.

Crows, almost universally exalted for their high intelligence, vary their calls according to what they want to say. They have calls to signal alarm, distress, and the desire to get together.

Even prairie dogs talk with each other and have regional dialects. Con Slobodchikoff of Northern Arizona University and his students decoded the alarm calls of Gunnison's prairie dogs and found that the prairie dogs emit different alarm calls for different predators, for coyotes, for dogs, for hawks, for humans, for example. The prairie dogs even vary their alarm calls to give physical descriptions of the predators. Slobodchikoff claims that their calls are like short sentences made of nouns and adjectives.

Researchers have recently discovered that every single animal on our planet has a unique voice. And, by studying sound spectrographs of their calls, researchers have concluded that many, many animals, both avian and mammalian, have different calls appropriate to different situations.

Everybody's talking! And we humans used to think we were the only ones.

But can the birds hear each other over the sound of trucks?

Can the whales hear each other over the sound of cruise ships, cargo ships, submarines, and aircraft carriers? If they can't, how will they ever find mates?

Noise pollution doesn't stop humans from making babies, but it may stop some of our planet's other communicative creatures.

To Cosmo, the sound of a truck backing up is not noise pollution. The truck's beeps, as well as the other sounds we industrious humans make with our machines, are noise pollution only to those of us who can remember or can imagine a time or a place without trucks, trains, ships, or planes.

Does a ninety-year-old Blue whale remember a time when he heard no ships?

For Cosmo, hatched in 2001, the sound of a truck is as normal a part of her world as the sound of a cardinal.

It's time for Cosmo to go to bed. After spending an hour speaking enthusiastically about feathers, fur, doggies, and birdies, interrupting her own monologue with barks and hoots and beeps and cheeps, quiet chuckles, and raucous laughs, Cosmo just told me: "Cosmo wanna cuddle. Cosmo wanna go to bed!"

But as I approached her, she raised her left foot and asked, "Betty Jean wanna kiss feet?"

I let her wrap her four toes around my nose. She chuckled. "Hehehehe." Then with her beak she yanked an earring off my left ear.

******************************************************************************************************

Here is a link to Cosmo's website and to Conversations with Cosmo.

Here is a link to the Publisher's Weekly review of Conversations with Cosmo.

". . . the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Nonhuman animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess these neurological substrates."

--The Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness, 2012